Editor’s Note:

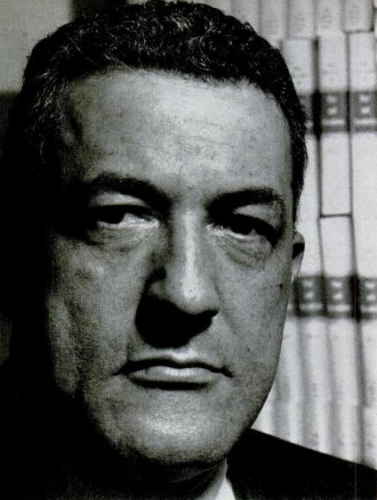

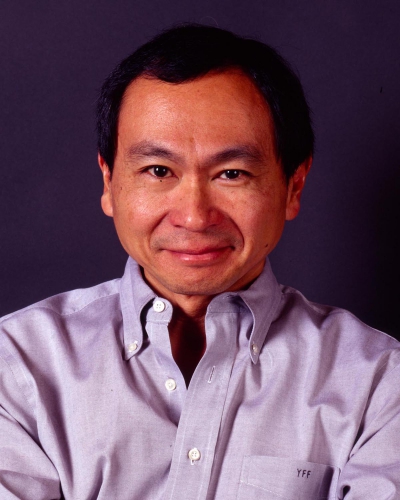

Lawrence Dennis (December 25, 1893–August 20, 1977) was one of America’s most original Right-wing critics of liberalism, capitalism, imperialism, and the Cold War. Interestingly enough, he was part black, a fact that was known to his many Right-wing admirers. In commemoration of Dennis’ birthday, and as a Christmas gift to our readers, we are reprinting Keith Stimely’s excellent introduction to his life and ideas.

Best known at the height of his writing career in the 1930s as “America’s leading fascist” and also as a strenuous opponent of American intervention in World War II, Lawrence Dennis was an economist and political theorist whose writings on the decline of capitalism and its international social and political implications received wide and serious attention in the 1930s and early 1940s. In fact, Dennis was much more than an apologist for fascism or a conservative isolationist, and in some of his ideas he could be viewed as a precursor as well as a contemporary of such better-known thinkers as John Maynard Keynes, Adolf A. Berle, Jr., James Burnham, Max Nomad, Charles A. Beard, and George Orwell. There is something of each of these thinkers in Dennis, and if because they and Dennis all published their ideas at roughly the same time, there arises any question of his intellectual “borrowing”[1] from them, it might be well to point out just who preceded whom.

Dennis’s initial formal statement of his ideas in 1932, in his book Is Capitalism Doomed?,[2] was almost exactly contemporaneous with Berle’s published statements of his concept of propertyless power[3] and Nomad’s notion of the inevitable entrenchment of a power-driven bureaucratic elite even in “workers’“ movements and societies proclaiming an end to all elitisms.[3] Dennis’s book appeared some ten years before Burnham’s work arguing for the theory of a new managerial elite replacing old business and even governmental elites,[5] and longer than that before Orwell’s depiction of psychological and actual preparation for international conflicts perpetually designed to serve domestic political ends.[6] Dennis published two years before Charles Beard made his case for America’s rejection of overseas investments with their inevitable political ties and his prescription for what would amount to “regional autarchy” for the nation’s economy,[7] and four years before Keynes’s final, published formulation, in his “General Theory” of 1936, of his rejection of the supposition of classical economics that the business cycle will always self-correct and his prescription for government stimulation when it does not.[8] Historian James J. Martin has remarked that all one has to do to find evidence of very many “Keynesian” ideas floating around American intellectual circles years before the General Theory is look at issues of the Harvard Business Review of the late 1920s. Keynes’s and “Keynesian” influences—if gradual—on theory and policy in the liberal-democratic states have always been recognized; much less treated has been the question of his influence on the fascist states, or the consideration and adoption by them of policies that bore strong similarities in their essences to what we would regard as “Keynesianism.” Martin has been responsible for bringing to general public attention the fact that Keynes wrote a special foreword for a translated edition of the General Theory which appeared in National Socialist Germany in 1936; see “J. M. Keynes’s Famous [sic: this is Martin’s dig] Foreword to the 1936 German Edition of the ‘General Theory’,” pp. 197-205 in Martin, Revisionist Viewpoints: Essays in a Dissident Historical Tradition (Colorado Springs: Ralph Myles Publisher, 1971; 1977).

Dennis himself was sufficiently honest in referencing the basic influences on his thought: the historian Frederick Jackson Turner, the sociologists Vilfredo Pareto and Robert Michels, the philosopher of history Oswald Spengler, the economists Thorstein Veblen and Werner Sombart. Out of his familiarity with these thinkers and his own experiences in the 1920s as a U.S. diplomatic service officer and an international banking functionary, he fashioned by the mid-1930s a synthetic view of economics, politics, society, and history that was striking at least in its sheer brilliance and clarity and which both liberal and conservative commentators of the time recognized as such, whether they agreed with it or not.

Dennis became even more provocative after he began actually prescribing possible political solutions to the problems of depression and war. Although the American and British left initially hailed Dennis as a leading expositor of capitalist senescence,[9] they became increasingly wary of him (though still giving his ideas wide play) when he turned in the mid-thirties to fascism and began to advocate for the United States a corporatist, collectivist state in which business enterprise, though retaining its basic forms and privately owned character, would have been obliged as necessary to knuckle under to the programmatic and channelizing demands of a “folk unity” state. Aside from the “dark” similarities between such a system and regimes of the time in Germany and Italy, this was too little for the left and too much for the right. New Dealers in particular were furious when Dennis blithely stated that trends toward such a political-economic system were already well under way in the Roosevelt regime, even in the absence of such blunt advocacy for them as he was wont to make.[10] Eventually Dr. New Deal himself in the guise of Franklin Roosevelt would have Dennis prosecuted under the Smith Act for “sedition,” and the economist joined 29 other assorted non-interventionists, of widely varying political hues and mindsets, in the dock for the “mass sedition trial” of 1944. Dennis was the principal among the defendants in consistently making a fool out of the prosecutor, and after a mistrial caused by the death of the judge, to the accompaniment of increasing skepticism about the whole business even within the pro-administration press, the government dropped its case.[11] By that time establishment opinion-formers had dropped Dennis, whose ideas were deemed beyond the pale. The man who once wrote for the Nation, The New Republic, Foreign Affairs, the Annals of the American Academy, Saturday Review, and Current History, whose speeches and participation in roundtable forums were covered by the New York Times, and whose books were given reasoned hearings by such luminaries as Max Lerner, Matthew Josephson, Louis M. Hacker, John Chamberlain, Dwight MacDonald, D. W. Brogan, William L. Langer, Waldemar Gurian, Francis Coker, Norman Thomas, Owen Lattimore, and William Z. Foster, was denied any further access to or treatment in “respectable” forums (or even in the “unrespectable” forums of the left, which reached a vast audience of thoroughly establishment intellectuals) and so had recourse to self-publication for most of the rest of his productive years.[12]

Dennis became even more provocative after he began actually prescribing possible political solutions to the problems of depression and war. Although the American and British left initially hailed Dennis as a leading expositor of capitalist senescence,[9] they became increasingly wary of him (though still giving his ideas wide play) when he turned in the mid-thirties to fascism and began to advocate for the United States a corporatist, collectivist state in which business enterprise, though retaining its basic forms and privately owned character, would have been obliged as necessary to knuckle under to the programmatic and channelizing demands of a “folk unity” state. Aside from the “dark” similarities between such a system and regimes of the time in Germany and Italy, this was too little for the left and too much for the right. New Dealers in particular were furious when Dennis blithely stated that trends toward such a political-economic system were already well under way in the Roosevelt regime, even in the absence of such blunt advocacy for them as he was wont to make.[10] Eventually Dr. New Deal himself in the guise of Franklin Roosevelt would have Dennis prosecuted under the Smith Act for “sedition,” and the economist joined 29 other assorted non-interventionists, of widely varying political hues and mindsets, in the dock for the “mass sedition trial” of 1944. Dennis was the principal among the defendants in consistently making a fool out of the prosecutor, and after a mistrial caused by the death of the judge, to the accompaniment of increasing skepticism about the whole business even within the pro-administration press, the government dropped its case.[11] By that time establishment opinion-formers had dropped Dennis, whose ideas were deemed beyond the pale. The man who once wrote for the Nation, The New Republic, Foreign Affairs, the Annals of the American Academy, Saturday Review, and Current History, whose speeches and participation in roundtable forums were covered by the New York Times, and whose books were given reasoned hearings by such luminaries as Max Lerner, Matthew Josephson, Louis M. Hacker, John Chamberlain, Dwight MacDonald, D. W. Brogan, William L. Langer, Waldemar Gurian, Francis Coker, Norman Thomas, Owen Lattimore, and William Z. Foster, was denied any further access to or treatment in “respectable” forums (or even in the “unrespectable” forums of the left, which reached a vast audience of thoroughly establishment intellectuals) and so had recourse to self-publication for most of the rest of his productive years.[12]

Dennis spent those years—a good quarter-century—vigorously opposing the cold war and any view of Soviet Russia as carrying a special “sin” that had to be wiped out, just as he had opposed American entry into World War II and any view of the fascist nations as unique repositories of “sin.” In both cases his positions arose less from ideological affinities than from his hard-core realism: his caution was against “the bloody futility of frustrating the strong.” He also continued to state his view that American capitalism, having lost its essential “dynamic,” including its necessary “frontier,” could not solve its endemic twentieth century problems—underconsumption and mass unemployment—without recourse to war or “permanent mobilization” for it. Sneering at all “classical,” “Austrian,” or “monetarist” solutions to capitalist crisis, he proclaimed—as one who had been among America’s foremost “pre-Keynes Keynesians”—that Keynesian-style government intervention in some form and to some degree or other was here to stay and was not a bad thing, provided that it focused inward, on the solution of the nation’s internal problems, and not outward, to “solution” by foreign war.

Ultimately Dennis believed that “economic laws”—whether those proclaimed by classical economists or Marxists—must and would inevitably follow political mandates, not vice-versa. In a modern age in which traditional capitalism was obsolete, socialism was not at all going to be what its utopian founding theorists had in mind, and the sheer power-wield of elites operating in nationalistic contexts through discreet psychological and cultural appeals was the decisive factor in shaping economic relationships. Toward the end of his life Dennis coined the term “operational”—as opposed to idealistic or wishful—to describe not so much what but how to think correctly about world problems, including economics, and he called himself an “operational thinker.”

That he had once called himself a “fascist,” however, has informed almost all the approaches to his thought up to the present. Always monumentally unconcerned with what most people, including fellow intellectuals, thought of him, Dennis in the 1930s frankly advocated a variant of a system that then seemed to be “working”—as American capitalism and liberal democracy, unable to pull themselves up out of the Depression, just were not. That the label of “fascist” (which, in its conventional use in America as a term of invective, has gone a long way toward meaning absolutely nothing from meaning absolutely anything) has stuck is in part although by no means exclusively the fault of Dennis himself. It is a label that has stood as a major roadblock on the way to serious considerations of the full range of his ideas, on their plain merits, from the perspective of history since they were first advanced. “America’s No. 1 intellectual fascist,” “Brain-truster for the forces of appeasement,” “the intellectual leader and principal advisor of the fascist groups”[13]—these were the epithets by which Dennis came to be identified, and is still in large part identified. But even in them there can be seen a nuance that not only applies to but was actually formulated just for him—“intellectual,” “brain-truster,” “advisor.” Even the shrillest critics could not bludgeon Lawrence Dennis into the prefabricated stereotypes as a native-fascist Bundist, Silver Shirt, or Christian Mobilizer. And even in recognizing Dennis as a genuine fascist intellectual, his critics also differentiated him further. Unlike most “philosophers of fascism,” who tended to restrict any consideration of economic issues to situational analyses, Dennis did not ignore economics in the construction and exposition of his larger, broadly historical, world view. Rather, his appreciation of fascism derived in good part from his initial economic orientation in approaching problems of politics and society, specifically in his critique of capitalist historical development in America.

A summary and analysis of that critique and of Dennis’s career are long overdue, as is a critical consideration of some of the historiographical and other scholarly treatments of Dennis that have appeared since the climax of his career. It was just around the time of his retirement from writing around 1970 that a younger generation of scholars began to study his thought and to bring him to the attentions of yet others for whom he was either a completely unknown quantity or just the smart guy of “the 1930s native-fascists.” Whereas older considerations of Dennis, coming from old-line liberals, focused on his political fascism, the newer studies, coming after the development of a “New Left” historiography critical of American interventionism abroad and from writers inclined toward or interested in anti-“consensus” intellectual history, have tended to concentrate on his consistency in opposing both American involvement in World War II and in the cold war. There has been no study devoted to his economic views; the most thorough treatments of these have been in reviews of his first three books as they appeared in the span of years between 1932 and 1941. The following purely expository treatment of Dennis’s leading economic idea—his “frontier thesis” for American capitalism—makes no claim of thoroughness either in itself or in placing his economic thought within the context of his broader views. It will serve as an introduction to all the basics of these, however.

The Man and a Theme[14]

Dennis was born in 1893 in Atlanta, Georgia, of moderately well-to-do parents. He attended Philips Exeter Academy from 1913 to 1915 and proceeded to Harvard University. His studies interrupted by American entry into the First World War, he volunteered and received his officer’s commission through attendance at the novel Plattsburg officer training camps in Plattsburg, New York, in 1915 and 1917 and subsequently served in France as a lieutenant of infantry with a headquarters regiment. For several years after demobilization he wandered around Europe playing foreign exchange markets “on a shoe string,” then returned to America to finish his studies at Harvard, graduating in 1920.

Dennis entered the U.S. diplomatic service and worked as American chargé d’affaires in Romania and then Honduras. He was sent to Nicaragua as chargé in 1926 and remained there throughout the Sandino revolution and the American military intervention. It was Dennis who, under State Department orders, sent the cablegram “requesting” the intervention of U.S. Marines in Nicaragua. He never favored the intervention and after publicly criticizing it in June 1927, resigned from the diplomatic service. He went to work in Peru as a representative of the international banking firm of J. & W. Seligman & Co., advising it on Peruvian and other South American loans. In this capacity he came increasingly to be wary of, and finally unalterably opposed to, loans for private or public purposes made without tightly-held strings attached or any loans to countries whose perpetually unfavorable balances of commodity trade made repayment a dubious proposition. He advised against weighty loans that were in fact made and on which the debtors in fact defaulted. In 1932, two years after resigning from Seligman to retire to his Becket, Massachusetts, farm to pursue a career as writer, lecturer, and investment analyst, he was a prominent witness before the Johnson Committee of the U.S. Senate investigating international lending practices and the default of overseas loans. By that time he was well under way to establishing himself in American intellectual circles as a sharp critic of investment banking practices and of an entire capitalist system which had evidently brought on—and so far could not solve—American and then worldwide depression. Articles in leading journals paved the way for the systematic, in-depth exposition of the viewpoint that he espoused for the rest of his life.

Dennis’s career as a thinker in the 1930s and 1940s was roughly divided into three phases, each represented by a book. In Is Capitalism Doomed? of 1932 he provided his basic critique of traditional capitalist business enterprise and pointed out the necessity of government planning. Chief among the abuses of private capitalist “leadership” was the grotesque over-extension of credit, internally in agriculture and industry and externally in foreign loans and trade (loans being made only to allow the paying-off of earlier loans, the same process then occurring with these later loans; trade actually being paid for only by the loans of the trader). Not far behind in iniquity was the refusal of capitalists to spend, preferring to hoard, the real incomes that accrued to them while millions were unemployed for want of investment spending. Not yet ready to state what, if anything, could or should take the place of this outdated business order and the liberal-democratic state which allowed it (the two necessarily went hand-in-hand, in his estimation), Dennis contented himself with providing “suggestions of moderation or restraint”—specifically, high taxation on the wealthy (preferably toward job-creating public works projects), high tariffs, and high government spending to keep up employment in a self-sufficient or autarchic national economy—which might prolong and render American capitalism’s “dying years” more pleasant. By 1936 and The Coming American Fascism[15] Dennis was ready to be even more specific both in diagnosis and prescriptive remedy. With the Depression still unrelieved six years after it had started and three years after inauguration of the Roosevelt “planless” revolution,[16] Dennis foresaw the system’s final collapse and offered only the alternatives of fascism or communism to replace it. He frankly favored the former, not only because it seemed to be proven by example in certain countries of Europe, but because the latter alternative would mean a disastrous “wipe-out” of valuable business technicians—as opposed to their co-option and enlistment in national service by a fascist state. Dennis did provide, at length, his description of what “one man’s desirable fascism” would be like—but he stressed that any successful fascist movement in America would doubtless not call itself that and in fact would most probably arise in the guise of anti-fascism, perhaps even in the crusading call for a war against fascism.

In The Dynamics of War and Revolution[17] of 1940, Dennis particularly explored this last theme as part of an overall treatment linking his ideas to the tempestuous international scene of the time. He predicted eventual American involvement in the European war as the only way for American capitalism finally to get out of its Depression, and as representing a desperate effort by the stagnated “Have” plutocrat countries (America and Britain) to stifle the rising economic as well as political challenges of the dynamic “Have-not” socialist countries (Germany, Italy, and Russia). His blithe identification of the Hitler and Mussolini regimes with the “socialist” camp tended to cause great upset in communist or other leftist reviewers of the book.

In The Dynamics of War and Revolution[17] of 1940, Dennis particularly explored this last theme as part of an overall treatment linking his ideas to the tempestuous international scene of the time. He predicted eventual American involvement in the European war as the only way for American capitalism finally to get out of its Depression, and as representing a desperate effort by the stagnated “Have” plutocrat countries (America and Britain) to stifle the rising economic as well as political challenges of the dynamic “Have-not” socialist countries (Germany, Italy, and Russia). His blithe identification of the Hitler and Mussolini regimes with the “socialist” camp tended to cause great upset in communist or other leftist reviewers of the book.

But the liberal states’ war to end fascism, with its necessary mobilization of business resources under governmental direction and backed only by government financing, all accompanied by massive doses of governmental propaganda to the democratic herds, would result only in an increasing impingement of “fascist” trends upon the political and business structures of those very states, and even—especially—in winning there could be no return to a laissez-faire whose era had passed. Dennis hoped that the state mobilization of the economy that he saw as inevitable, and which he favored on principle, could be directed inward to reform, public works, and ultimate national economic self-sufficiency. Were it to be directed outward in another big foreign crusade ostensibly to end “sin” in the world, it would probably continue to follow that course so lucrative for keeping up production, maintaining high employment, and staving off deflation, and more “sin” would assuredly be found to crusade and spend against after the dispatch of “original sin.” Thus, even before American intervention in the war (right during the Phony War, in fact), and with no real clues as to its outcome or even the final line-up of adversaries, Dennis was hinting at a postwar cold war for America.

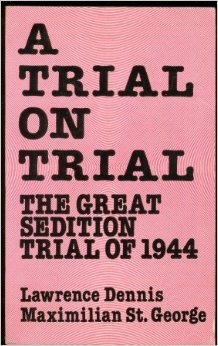

He supplemented his book-writing activities of the 1930s and early 1940s with regular contributions to H. L. Mencken’s American Mercury, where many of the ideas of The Coming American Fascism and The Dynamics of War and Revolution were originally advanced, lectures and debates, consulting in economics for E. A. Pierce & Co., and editing and writing his own newsletter, The Weekly Foreign Letter, which ran from 1938 to 1942. After the “sedition” episode and a lengthy book about it, A Trial on Trial (co-authored with lawyer Maximilian St. George), he started another newsletter, The Appeal to Reason, which ran for more than twenty years, despite a circulation that never exceeded 500 subscribers (who included former President Herbert Hoover, Senator Burton K. Wheeler, General Robert E. Wood, General Albert C. Wedemeyer, Amos Pinchot, Colonel Truman Smith, and Bruce Barton).[18] Dennis also served as an investment advisor to General Wood and made him a lot of money. Dividing his time after the war between his Massachusetts farm and the Harvard Club in New York City, he confined his social life largely to a small circle of friends and colleagues, which included revisionist historians Harry Elmer Barnes, Charles Callan Tansill, and James J. Martin, political scientist Frederick L. Schuman (his neighbor in Massachusetts—and political opposite-number; also his in-law), writer and former “sedition” co-defendant Georqe Sylvester Viereck, and publicist H. Keith Thompson. His last book, Operational Thinking for Survival, appeared in 1969. Although the basics of the manuscript had been completed in the late 1950s, the book lay fallow for want of a publisher.[19] In it he hewed to his basic convictions as expressed 30 years before; he claimed vindication by the course of postwar events, made the extended case for “operational” (“or ‘rational’”) thinking, described the futility, waste, and danger of a cold war that was both a result of and a constant prop for moralistic stupidity, and found time to blast neo-classical critics of the “New Economics” of which he had been one of the earliest, if most unusual, exponents. Shortly after the book’s appearance, he suffered an incapacitating stroke and remained only sporadically active until his death in 1977.

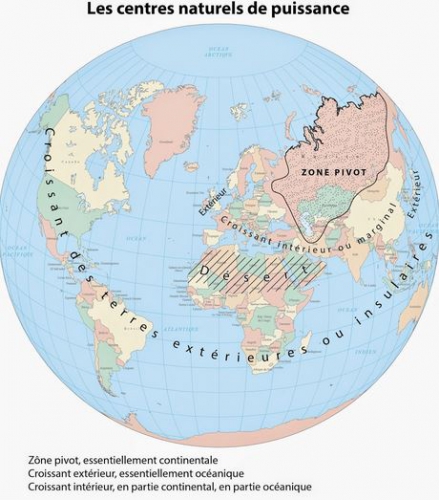

Dennis’s most systematic and developed presentation of his fully matured ideas on the decline of capitalism appeared in The Dynamics of War and Revolution. In Part II, “The End of the Capitalist Revolution,” consisting of five chapters, he laid out his “autopsy” of the American—in microcosm, the Western World’s—capitalist dynamic. Capitalism, Dennis argued, must ever expand or die. The impulse, the driving dynamic, behind expansion is the eternal quest for markets (of need, not just luxury), a quest that is actually a desperate race against the threat of a linear process of overproduction, causing underconsumption, causing cutbacks in production, causing unemployment, causing loss of purchasing power, causing loss of investment incentives—all leading to stagnation and, finally, bust. Busts may be followed by booms only when real market expansion takes place. But such expansion can occur only when a perpetual, ever-receding “frontier” is present. The frontier can be a literal, geographical frontier (far from, contiguous to, or even within a nation), or the “frontier of scarcity” provided by a growing consumer population, or the “frontiers” provided by other nations or regions whose markets can be seized without excessive political or military risk. The three centuries of the “Capitalist Revolution,” roughly from 1600-1900, satisfied the need of capitalism in all these areas and provided its dynamic power. The discovery of a vast New World provided Europe’s literal frontier for expansion of its markets (and its population), as well as sources of materials for production and distribution (mercantile considerations were in fact the single most significant impulse behind the drive for colonization); within that New World, both before and after it was constituted as a new nation, the westward frontier provided the same engine of dynamism for the base population—especially in the lure of free land. All over the globe European imperialisms found markets “for the taking” in lands which could not stand up to European military technics or trading attraction; America also expanded its national and market frontiers through “easy wars of conquest”—against Mexico, against Spain in contests of rival imperialisms, in interventions and “presences” all over its southern watches and even in the far Pacific; the new technics of industrialization and transportation came along at the perfect moment to exploit the situations of these expanding market-frontiers, and all these developments were accompanied by an overall burst in population growth such as the world in its recorded history had never before experienced.

Thus the “Capitalist Revolution” was successful because of specific, historically conditioned reasons. But according to the theoretical apologists for capitalism, the success was not historically conditioned, and there was no reason why it could not continue indefinitely and the revolution remain permanently, even if it were erratic in its equilibrium: Busts would always be followed by booms in a self-correcting business cycle. Once stagnation or bust were reached, new consumer demands would before long “force” investment and production to rise again (and thus employment, purchasing power, more investment, and so on). The proponents of classic capitalism were continuing to assert this right down through the depths of the 1930s Depression. For Dennis, these rosy theorists were wrong and had been proven wrong by an American (and out of it, a world) economic cataclysm which had not been seen before and after which things would never be the same again. The theorists were basing their prescriptions and predictions on the historical record of the business-cycle through the 300 years of capitalist dynamism, as if universal or timeless “laws” of business-development could be deduced from that alone. In fact, by their concentration on the “waves” of the business cycle in this limited time-period and historically unique situation they were missing the tide. The great tide was the fact that the “Capitalist Revolution” was finally over because the frontier—all the “frontiers”—existed no more.

The literal American frontier—which had provided the essential stimulus of “the profits of free lands” (both as lure and, crucially, as escape)—ceased to exist about 1890. Linking this in with British imperialism, which had reached its apogee at about the same time (“the frontier was to Americans what the empire was to the British”[20]), Dennis held that the processes of expansion and acquisition, not the actual holding, constituted the mechanism that gave capitalism its dynamic; the former fueled capitalist development, the latter inevitably invited stagnation:

Empire is a process of expansion by conquest, not just the place so acquired. . . . The socially important fact about an empire is getting it, and, about a frontier, getting rid of it. The two processes amount to the same thing . . . so far as empire is concerned, it is the growth, not the existence, the getting, not the keeping, that is historically significant and socially dynamic. A nation grows great by winning an empire. It cannot remain great merely by keeping one. Indeed, once it stops growing it will start decaying . . . . Mankind is destined to live by toil and struggle, not by absentee ownership . . . . What we now call capitalism, democracy and Americanism was simply the nineteenth century formula of empire building as it worked in this country. Here the process was often called pioneering; its locus, the frontier . . . . Now that empire building along the lines of the nineteenth century formula is over, both for the British and ourselves, capitalism and democracy are over as we knew them in that past era. . . . Unlike the Have-nots, we shall not expand because we are land hungry. Hunger is dynamic. In the twentieth century, unlike the nineteenth, no profit is to be made out of increasing available supplies of raw materials and foodstuffs. Profit making is dynamic. But, to be dynamic it has first to be possible. The conditions creating this possibility are the primary dynamisms of capitalism.[21]

The conditions that imparted success to capitalism were gone with the frontier, and for Dennis the central idea of historian Frederick Jackson Turner, which he quoted approvingly—”The existence of free land, its continuous recession and the advance of American settlement westward, explain American development”[22]—explained in particular the character of American economic development, just as the “world frontier” with its “free” (or easily-acquired) land for European nations explained broad capitalist development. But the end of capitalism could also be explained. The end of the literal frontier for America and the capitalist world was paralleled by the end of the industrial revolution, the decline in the rate of population growth, and the end of further possibilities of “easy wars of conquest.”

The industrial revolution—the effect of technological change—had worn down, and there could be no hope that industrialism or technics could always exist, through evolutionary refinements of better techniques and types of production and more and different appeals to the marketplace, to “reinvigorate” or “save” capitalism when necessary. Industrialism had worn down because it was never a dynamic of itself, but could be dynamic only in the era of the frontier and of rapid population growth. (“Today, so far as stimulating business expansion is concerned, industrial changes are no more dynamic than changing cross ties or steel rails on a railroad. . . . As for entirely new products, they now tend to replace old products and to result in no net increase in consumption or production.”[23]) The essence of the industrial revolution was change specifically within the context of growth or continuous expansion, which means that it could only have been a transient phase whenever and wherever it occurred. This “series of events in time and place” constituted a very real revolution, perfectly following the mercantilist one and necessary to the realization of the overall capitalist one—but it could remain revolutionary only so long as it was expansive.

The industrial revolution—the effect of technological change—had worn down, and there could be no hope that industrialism or technics could always exist, through evolutionary refinements of better techniques and types of production and more and different appeals to the marketplace, to “reinvigorate” or “save” capitalism when necessary. Industrialism had worn down because it was never a dynamic of itself, but could be dynamic only in the era of the frontier and of rapid population growth. (“Today, so far as stimulating business expansion is concerned, industrial changes are no more dynamic than changing cross ties or steel rails on a railroad. . . . As for entirely new products, they now tend to replace old products and to result in no net increase in consumption or production.”[23]) The essence of the industrial revolution was change specifically within the context of growth or continuous expansion, which means that it could only have been a transient phase whenever and wherever it occurred. This “series of events in time and place” constituted a very real revolution, perfectly following the mercantilist one and necessary to the realization of the overall capitalist one—but it could remain revolutionary only so long as it was expansive.

It might be expansive in perpetuity if “Say’s Law”—production as necessarily creating the purchasing power to pay for what is produced—was correct. It was not correct, because its essential corollary, the doctrine of “consumer sovereignty” holding that goods and services are produced for a profit in response to consumer needs and demands, was “100 percent false. Producer demand, not consumer demand, is sovereign.” Here Dennis turned on its head one of the fundamental tenets of capitalist theory:

The producers decide what, when and how much to produce, including the volume of construction and producer goods activity such as new plants, office buildings, etc. In other words, volume and rate of reinvestment of profits and savings determine swings in consumer demand. Producers and investors determine swings in the volume and velocity of the flow of consumer purchasing power. Booms are made by producer and investor optimism and ended by producer and investor pessimism. Consumer needs and desires have no more to do with the up- and downswings than sunspots. When producers decide to curtail production, consumer purchasing power declines and thus arise good reasons to cut production and employment and wages still further. The process is reversed by a change in producer and investor psychology. The producer decisions, as every one knows, are governed mainly by changes in expectations of profit.[24]

The end of the frontier—even just catching sight of the end before it was reached—changed the expectations of the “sovereign producers.” That is, it changed their willingness to risk investment. The chief characteristic of American business organization, as it resulted from the industrial revolution taking place in a dynamic frontier-context, was monopoly—about which, incidentally, “there is more hypocrisy . . . than any other subject in the whole field of economics.”[25] The industrial revolution and the frontier created monopolies in almost every new industry. At the beginning and through the halcyon days of the revolution, the monopolistic entities, existent or in process of formation, were the very ones that were most committed to and enthusiastic about investment and risk, and against hoarding or minimal-risk investments or operations. By the end, they were tending to be hoarders or “safe operators” who would expand vertically or horizontally, often both, in organization and control but not in actual new market risk and production—because market frontiers were no longer expanding. This caused gradual stagnation and, when combined with the run of “artificial” expansion of the 1920s, finally Depression. The short-lived boomlets since 1929—those of 1933, of late-1936/early-1937, mid-1938, and late-1939—only provided more evidence that industrial expansion was over as an upholder or as a rescuer of capitalism; they were caused by fears of inflation, not at all by expectations of profits from industrial expansion. Such expectations as could cause real boomlets, not to mention a real end to the Depression, could occur only in a recognized “frontier” situation. Dennis considered at length, and rejected wholesale, the argument (“if it is to be dignified by that name”) that even with the end of the geographical frontier and thus of a physically expanding market base, there nevertheless existed and would always exist a limitless “frontier” of unsatisfied human wants and needs and discoveries which would provide all the incentives and opportunities to keep capitalism going. This argument, as “Say’s Law” and its corollary, assumed that “consumer desire instead of producer greed” was the dynamic of capitalism. But the key was in fact “producer greed”–and although that might happen to satisfy human wants and needs, even in great volume, in the course of the quest for private gain, such a result

. . . was purely an incidental and, in no sense a dynamic or causative factor in these processes. As long as supplies of land, labor and natural resources becoming available for exploitation were rapidly increasing, there was a constant shortage of capital, machinery, housing, transportation facilities and means of subsistence for the workers. This shortage constituted a real industrial frontier. It was a frontier of need, not luxury. Capitalism needs a frontier of scarcity which will keep interest rates high and profit margins wide. It cannot flourish on a frontier of industrial abundance in which interest rates would drop to zero and incentives to private investment would virtually disappear.[26]

One “frontier of scarcity” that was necessary to a successful capitalism was simply the existence of more and more bodies that needed food and goods. This “frontier” might last forever if population increase could be guaranteed in perpetuity. It couldn’t. Reviewing the census statistics from the first national census in 1790 through that of 1930, Dennis saw that, while the American population increased at dramatic rates throughout the nineteenth century, from roughly the end of the century on the rate of growth (though not simple growth) had been decreasing dramatically. The apogee of population growth, then, had been reached with the passing of the frontier. If the rate continued to decline, and Dennis assumed that it would without significant interruptions,[27] the consequences would be enormous for American capitalism—more so than they already were. For capitalism, here as in all other areas, needed growth:

One “frontier of scarcity” that was necessary to a successful capitalism was simply the existence of more and more bodies that needed food and goods. This “frontier” might last forever if population increase could be guaranteed in perpetuity. It couldn’t. Reviewing the census statistics from the first national census in 1790 through that of 1930, Dennis saw that, while the American population increased at dramatic rates throughout the nineteenth century, from roughly the end of the century on the rate of growth (though not simple growth) had been decreasing dramatically. The apogee of population growth, then, had been reached with the passing of the frontier. If the rate continued to decline, and Dennis assumed that it would without significant interruptions,[27] the consequences would be enormous for American capitalism—more so than they already were. For capitalism, here as in all other areas, needed growth:

First among the functions of population growth is that of creating a perpetual scarcity of bare necessities, so necessary for a healthy capitalism or socialism. This scarcity furnishes incentives for the leaders and compulsions for the led. This scarcity now affects only the Have-not countries; hence they alone are dynamic today. Capitalism in America was dynamic while world population increase assured food scarcity. Now that we have food abundance, capitalism is no longer dynamic. Hence the unemployed go hungry because we now lack scarcity. This explanation may sound paradoxical. Well, so is the situation in which farmers languish for buyers of their food and the jobless languish for food. . . . The nineteenth century way of averting the evil of abundance was to have large families. The twentieth century way, now that we have small families, is to have large-scale unemployment and two world wars in one generation. Given the ideology of democracy and capitalism making thrift a virtue and given the shrinking size of families, it is hard to see any way of coping with abundance other than unemployment and war. And given our culture pattern, it is hard to see how we can operate society without the compulsions of a scarcity which a high birth rate, unemployment or war alone can maintain for us in a sufficient degree under our system.[28]

Capitalism “in its era,” product of peculiar historical circumstances that combined to create a 300-year revolution, was insatiable in its thirst for markets precisely because its new productive and distributive power eventually sated the market’s thirst for products. But arrival at the ultimate point of satiation could be and was postponed, and the other factor that allowed for this, besides an expanding frontier and an expanding population to settle that frontier, was the expansion of markets through “easy wars of conquest”; these could guarantee the “scarcities of need” required to hold off stagnation or get out of depression. Wars, of course, had always been God’s gift to capitalism in stimulating production and soaking up unemployment; they thus provided more immediate benefits as well as their longer-term benefits in creating markets. But there was more to the war-imperative of capitalism than simple economic drives. In fact, “easy wars of conquest” fulfilled the needs not only of private capitalism but of public democracy. Capitalism would not have been what it was without democracy, and vice-versa. American democracy was founded on the twin pillars of a mercantile plutocracy and an agricultural slavocracy. The defeat of the latter in civil war meant only meant its absorption into a new industrial wage-ocracy. This wage-ocracy, called “mass employment,” was dependent for its very existence on the expansion of markets—that is, on the reality of frontiers; it naturally made this dependence felt in its political pressures. And the American democratic faith that was instilled into the mass-employed and employers alike was essentially faith in a perpetual land boom. By its national policies of settlement, of incentives for investment, of trade, and of war, the democracy could “keep the faith.” The democracy also had its own, more purely political, reasons, most nakedly seen in its war policies, for keeping it. While capitalism needed wars for foreign markets, land-grabs, and immediate productive stimuli, democracy needed wars for a social unity and stability at home that capitalism itself tended to disallow or disrupt:

In any brief review of the dynamic function of easy wars in the successful rise of capitalism and democracy it would be a serious omission not to call attention to the fact that nationalistic wars tempered the anarchy and contradictions of private competition. Both war and religion necessarily impose collective unity. Their practice unites large numbers of people in interests and feeling. Private competition, on the contrary, must always tend to destroy social unity. . . . An entire community can practice competition in an orderly way only in war or in competition with an outside community. Thus, in war-time, each warring community operates internally on the basis of cooperation and externally on the basis of competition. In this way there is order within and anarchy without. It is obviously an inevitable condition of any society of sovereign nations that it be characterized by anarchy. Multiple sovereignties are merely a synonym for anarchy. International anarchy is a corollary of national sovereignty. That numerous company of idealists and theorists who profess to wish to substitute in the international sphere the rule of law for the rule of anarchy while at the same time preserving national sovereignty is composed of persons who are either singularly obtuse or intellectually dishonest. Anyone who does not understand that, under the rule of law, there can be but one sovereign, not several, does not understand the meaning either of law or sovereignty.

But, although war has been throughout history a force for anarchy as among nations, it has been a force for social cohesion and order as within nations. Between chronic international anarchy and national order there is no necessary contradiction. The fact is that capitalistic democracies have needed the centripetal force of foreign warfare to offset the centrifugal force of private competition. . . . Individualism, or the disuniting force of private competition, has made this [traditional] need of foreign war all the greater. The free play of individual or minority group self-interest tends to make any community go to pieces. The counter forces of unification necessary for social order under capitalism have had to be largely generated by the continuous waging of easy and successful foreign wars.[29]

The problem now, in the twentieth century, was that the “easy wars” had gone the way of the frontier land boom and the frontier-filling population boom; their era was over.

With gusto, Dennis presented tabulations of the wars and military interventions of the three great capitalist democracies in the century and a half up to and including the 1920s. His summaries of these tabulations were meant to lend weight to his premises and conclusions—and to make the reader pause upon hearing any such phrase as “the peace-loving democracies.” England: “54 wars, lasting 102 years, or 68 per cent of the time.” France: “53 wars lasting 99 years, or 66 per cent of the time.” America: “In 158 years there was warfare practically all of the time.”[30]

The end of the era of “easy wars,” which came with the gobbling of the remaining easy marks on the world chessboard, completed the processes ending the “Capitalist Revolution.” The four great props of American capitalist democracy had finally all been knocked out: the frontier, industrialism-as-revolution, population growth, easy wars.

Without these props could American capitalist democracy survive? Dennis said that it could not, and he offered four possibilities as to what would happen to it:

(1) It could proceed in the old ways and under the old assumptions, perpetuating stagnation, massive unemployment, utter failure in every economic realm, and finally calling forth anarchistic chaos.

(2) It could succumb to an underclass proletarian revolution led by its own overclass of disaffected bourgeois out-elites, wiping out all forms of capitalism, and a lot of capitalists, in instituting the dictatorship of the intellectuals.

(3) It could be subsumed into an overall nationalistic, corporatist, and ethically collectivist state which would assume authoritarian directional control over, though not outright ownership of, much of the business apparatus and engage in necessary redistribution and reprioritization to end overproduction and unemployment, specifically via massive internal pyramid-building and social projects; this would be “socialism” in fact—whether its proponents or opponents wished to call it “fascism.”

(4) It could seek to prolong itself by the expedient “out” of war—which, now that there were no more “easy wars” to be had, would have to be a “hard” war, a really big show, the very staging of which, however, would necessitate to some significant degree the organizational and political steps mentioned in course number three.

Dennis favored the third course for America, but he saw the fourth as most likely. In late 1939 and early 1940, as he wrote, it was beginning to be put into effect. The new style of “hard” war had already been seen in the First World War, which originated in part in the clash of rival capitalist imperialisms. After that war, however, the emergence of revolutionary “socialist” regimes—whether Communist, Fascist, or Nazi—in the nations that walked out of the settlement of the war with status as Have-not countries brought forth a new possibility: that the next big war would not be one of clashing capitalisms, but a gang-up of the capitalist democracies (all in the same Depression boat, after all) against the “socialist” nations. That these “socialist” powers had their own grievances against the post-World War I democratic-imposed order, and were sufficiently dynamic and aggressive to do something about them, ensured that they could be held up to the democratic masses and democratic assemblies as violators of international “order” and “peace,” even of “civilization” itself; there would be no lack of “causes” of such a war, or rationales for it. The Have-not powers were dynamic indeed—as only nations unsated could be—and were not just redrawing European (and, in the case of Italy, colonial) borders, but smashing capitalism in Europe: reorganizing whole systems, redistributing wealth and authority, gaining autarchy and taking their nations out of the capitalistic “international systems” of trade and money. All this dynamism was in the name of nationalistic folk unities, “socialisms” in fact whatever the name, which had no further use for the subordination of national wills and destinies to private business or other interests.[31]

This is how Dennis saw the big war-in-the-making as of 1940, when Stalin, Hitler, and Mussolini formed a vague (but no less significant for that) “socialist” camp, against which stood the plutocratic capitalist democracies of Europe, with the biggest plutocratic capitalist democracy of all waiting in the wings fairly chafing to get in just as soon as that could be arranged. It would be another crusade, sold to the American herd in its favorite terms of world morality, but really a way for the Old Order at home—the order of a spent capitalism and a desperate democracy—to salvage itself by fighting the new revolution abroad:

The new revolution everywhere stands for redistribution and reorganization in line with the technological imperatives of the machine age. The cause of the Allies is that of counterrevolution. It upholds the status quo and opposes redistribution according to the indications of need, capacity for efficient utilization of resources and social convenience. It seeks to reverse in Europe the dominant trends, technological and political, of the past century and, more particularly, of the past two or three decades. The democracies have displayed their inability to utilize their resources in a way to end unemployment. But they now propose a crusade in the name of moral absolutes to prevent world-wide redistribution of raw materials and economic opportunities. The real issue before America may be stated as being one of achieving redistribution at home or fighting it abroad. The plutocracy that opposes redistribution at home is all for fighting it abroad. And the underprivileged masses who need redistribution in America are dumb enough to die fighting to prevent it abroad. The probabilities are that we shall have to come to the solution of the domestic problem of distribution through a futile crusade to prevent redistribution abroad. If it so happens, it will prove the final nail in the coffin of democracy in this country. And it should call for a terrible postwar vengeance on those responsible for this great tragedy of the American people.[32]

Regardless of whether they gained victory in the coming crusade or not and regardless of whether the victors took vengeance on the vanquished afterwards, American capitalism and its democracy were going to emerge from the struggle changed. The booms of war, and the war booms, were really the last tolls of the bell for the “Capitalist Revolution,” the 300-year product of frontiers that had been reached. The revolution that would follow might come by direction or indirection, be sudden or evolutionary—encompass at once or gradually all the changes in politico-social organization and direction that Dennis, for one, found desirable, or not. But definitely a revolution was in the making, and historians would eventually understand the outcome of this war, like its genesis, as differing profoundly from those of other wars when capitalism was in its prime. The post-capitalist era—no matter that many and even important vestiges of capitalism might remain for a long time yet—had arrived, and it would entail tremendous changes, in the realm of economics specifically, but extending into many other realms as well. It would and could mean, above all, the obliteration of the distinctions between public and private. For Lawrence Dennis, this was not undesirable or dangerous of itself –so long as it amounted to a melding basically in favor of the interests of the public. The specter against which he warned and fought by his words, and after the war saw as happening in fact, was that of this new reality being joined, out of the desperate efforts of capitalist democracy to prolong itself, by obliteration of the distinctions between the national and the international, and ultimately between war and peace. Could American capitalism, after a Second World War, really afford real peace? Could it face “honestly”—or, indeed, with any hope of success—such huge postwar problems as deflationary debt reduction, flooding of the available labor market, loss of political unity at home, of a “them” abroad, saturation of the home markets, massive reconversion of industry, and many others? Or would it continue to side-step its endemic problems via the classic “out” of war—even war that was not really war in the old sense (but not peace in any sense either)? A “cold” war would make up what it lacked in compressed intensity by occasional flashes of action around the globe, a global military spread-eagle in constant preparation for real conflict, a global political and economic presence as excuses for such conflict, and a very long life—perhaps limitlessly long.

Charles A. Beard, sardonically and bitterly describing in 1948 the practical consequences of the Roosevelt-Truman foreign policies as those policies became a “consensus” through the vaunted spirit of “bipartisanship,” said that America was now engaged in the pursuit of “perpetual war for perpetual peace.”[33] Dennis agreed with that, and would use the phrase (which gained wide currency as the title of a revisionist study of Roosevelt diplomacy) himself occasionally. Had it been up to him to coin it, he might have put it this way: perpetual war to stimulate production, soak up unemployment, create markets, and rally ‘round the people. Or, more briefly: perpetual war as substitute for the lost capitalist frontier.

Some Appraisals of Dennis

It took about a decade after World War II for Dennis to be considered once again in intellectual rather than polemical terms relating to the issues of the war. In considering radical political currents in his 1955 book American Political Thought,[34] political scientist Alan Pendleton Grimes treated “American Fascism: Lawrence Dennis” as an ideology and its spokesman called forth by the Depression. Grimes focused on Dennis’s identification of capitalism with democracy not only in historical parallel but in contemporary reality. Unlike the populist and progressive reformers, who tended to see capitalism (at least the “bad” capitalism practiced by the robber barons and trust spinners and holding-company pyramiders) as conflicting with or even antithetical to democracy, Dennis held that they went hand-in-hand. As an elitist, he wished to smash both, not reform either. In Grimes’s view, the major burden of Dennis’s fascist criticism actually fell not upon democracy but upon laissez-faire capitalism; democracy was criticized because it permitted the follies of capitalism, of private business leadership. The motivations of this business leadership, being purely selfish and directed toward the satisfaction of greed, were bound to conflict with the normal requirements of social development and order. With the passing of the frontier and opportunities for a kind of social-spiritual growth alongside business growth, the inherent conflict between society and business came out into the open and would have to be resolved one way or another. The era of the frontier, of America’s “militant nationalism” that allowed for a mass spiritual and non-commercial, even communitarian, impulse in expansionism to exist alongside mere business greed, had given way to mass atomism in a society now totally dominated by business greed (and made to suffer for business stupidity). Laissez-faire economic liberalism in theory and political democracy as it was put into practice were not equipped to handle the situation; therefore they had to be replaced.

Grimes considers Dennis’s critique of capitalist-democratic society to resemble Thomas Hobbes’s view of the state of nature: a war of all against all, of parts against parts and the whole. The laissez-faire system by which the state, the supposed guarantor of the public good, did not intervene in these struggles—or intervened occasionally only because some interest group had temporarily succeeded in gaining leverage within the state to the disadvantage of other groups—was plainly irrational. Moreover, this state-sanctioned chaos was carried on under an ethical umbrella of the highest fraud and hypocrisy, namely that of the legal system. This system promised “a government of laws and not of men.” For Dennis, this notion was pure fiction. Belief in it led to false hopes that “the peoples’ will” could ever be expressed through it and ignored the fact that the interpretation and administration of laws, not laws themselves, were what counted. At any time “the law” would and could mean only just what those elites in control of its application wanted it to mean. In America, and throughout American history, the elites in power were generally the capitalists and their partisans; the “independent” judiciary in a government of “separation of powers” was a myth. Also mythical was the notion of “freedom” as existing within the law—freedom, that is, as the natural condition in the absence of governmental restraint. Force and coercion were omnipresent, and it made little difference to those coerced whether force was applied by the government or by the “free” market. If, for instance, a person seeking work found no jobs as a result of decisions by private capitalists, then he was as coerced into unemployment as if there were a law against employment. Grimes quotes Dennis: “The much vaunted freedom of modern capitalism is largely a matter of the freedom of property owners from social responsibility for the consequences of their economic decisions.”

Grimes devoted about the last half of his sub-chapter on Dennis to discussing his more purely politico-philosophical ideas on elite rule, outside any economic context. That Grimes began his consideration of Dennis with the capitalist-democratic linkage demonstrates his awareness of the importance of economics in the genesis of his subject’s thought. His 1955 treatment represented the first step on the way to taking Dennis as seriously as book reviewers had once done, before the advent of war and “sedition.”

Grimes’s fellow political scientist David Spitz, in the considerable sub-chapter on Dennis in his Patterns of Anti-Democratic-Thought,[35] also took his subject seriously. But Spitz made no mention whatever of the anti-capitalist element in Dennis’s political thought and concentrated instead on his general theory of “The Elite as Power.” This exclusion is not to be criticized, since Spitz’s book deals only with political theory. But his criticisms of Dennis would have been more nearly complete if they had treated the real-world practical underpinnings, as Dennis saw and interpreted them, of that theory. Dennis’s views of economics and his economic analysis lay in the category, and to treat Dennis’s theory of the elite without discussing his extended critique of a real, historical elite-in-power—America’s capitalist elite—is to deny the analysis a significant part of its rationale. Spitz, at any rate and after a lengthy study of Dennis’s political theory, rejects it even though he grants the possible truth of its premise, that elites always rule. They may, says Spitz, but Dennis was wrong in supposing that this is necessarily incompatible with democracy, that the elite must always be an irresponsible elite.

For Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., writing in 1960, Lawrence Dennis “brought to the advocacy of fascism powers of intelligence and style which always threatened to bring him (but never quite succeeded) into the main tent.” Schlesinger devoted five pages to Dennis in the third volume of his The Age of Roosevelt, in a chapter on “The Theology of Ferment” that discusses various radical stirrings and personalities, left and right, thrown into some prominence during the Depression.[36] After considering the “literary fascists” Seward Collins and Ezra Pound, who were “figures in a sideshow, without significance in American politics,” Schlesinger turned to Dennis as the one fascist thinker who did possess real potential significance. Obviously admiring and noting Dennis’s Is Capitalism Doomed? as a “closely argued” attack on investment banking policies, Schlesinger nevertheless found beneath Dennis’s pose of cold realism notes of “romantic desperation,”[37] and he quoted a lengthy statement of Dennis from an unidentified private letter: “I am prepared to take my medicine in the bread line, the foreign legion, or with a pistol shot in the mouth. . . . I should like nothing better than to be a leader or a follower of a Hitler who would crush and destroy many now in power. It is my turn of fate now to suffer. It may some day be theirs.”[38]

Turning to The Coming American Fascism, Schlesinger noted the ease with which Dennis assumed that a variety of fascism could come to power and be successful in the United States: big business organization as well as the ingrained docility, standardization, and regimentation of the American people, who were already the world’s biggest suckers for advertising, propaganda of all kinds, and press and radio domination, made no other country “better prepared for political and social standardization.” As for their traditions of and a supposed passion for “freedom,” 90 per cent of the American people had no grasp “whatever” even of what their own ideological system was supposed to be all about. Therefore, according to Dennis, “A fascist dictatorship can be set up by a demagogue in the name of all the catchwords of the present system.”[39] Schlesinger went into some detail about the various particulars of Dennis’s vision of a fascist America. As to what and who could realize that vision and make the revolution, he considered the importance of Dennis’s idea of “the elite.” Here Schlesinger noted that Dennis was sometimes vague, sometimes contradictory, about just who constituted the fascist “elite” or, precisely, the latent fascist “out-elite” that desired power.[40] But there was little doubt as to the constitution of the particular societal group or class on whose behalf the elite would be working: the revolutionary dynamic would come from the “frustrated elite of the lower middle classes” who were threatened with being “declassed.”[41] Schlesinger took Dennis at his word when the latter said that he harbored no personal political ambitions, but he saw in him (and supposed that Dennis saw in himself) the qualities of a Goebbels, of a very smart brain-trust man who could serve a real fascist demagogue in justifying a revolution:

His style was clever, glib, and trenchant. His analysis cut through sentimental idealism with healthy effect. He tried to shift attention from words and symbols to the realities of power. His ‘realistic’ writing, for all its flashing and vulgar quality, had an analytic sharpness which made it more arresting than any of the conservative and most of the liberal political thought of the day.[42]

But a truly influential fascist demagogue never developed in America (Huey Long, for whom Dennis expressed admiration as “. . . smarter than Hitler, but he needs a good braintrust,”[43] might have become one), and Dennis was left to conjure intellectual rationales for an American fascism that existed more in the world of myth and wish. “Goebbels, after all, had a government to transform dreams into reality, and Dennis, only the Harvard Club,” Schlesinger wrote.[44] As for the existing reality of American fascist activists, who were of the mentality to agree with him without necessarily being able to comprehend him, Dennis had “progressively to lower his sights” in order to reach them. Seeing himself as “the sophisticated spokesman of a revolutionary elite in a technological epoch,” Dennis, like Seward Collins, found to his chagrin that the “elite which was to save civilization eventually turned out to be a collection of stumblebums and psychopaths, united primarily by an obsessive fear of an imaginary Jewish conspiracy. What began as an intimation of the apocalypse ended as squalid farce.”[45]

In his 1967 memoir Infidel in the Temple,[46] journalist and commentator Matthew Josephson reflected for a few pages on his acquaintanceship with Dennis in the 1930s. Josephson was already familiar with Dennis’s testimony in the 1932 Senate banking investigations and his arguments in Is Capitalism Doomed?, and having heard that Dennis was one of a number of pro-fascist intellectuals who regarded Huey Long as the potential Duce of an American fascism, he sought Dennis out in the Harvard Club for an interview, which his memoir largely sticks to recounting. “Trenchant in speech and as vivacious as I had been led to expect,” Dennis launched into a candid and freewheeling discussion of his beliefs and their origins. Quoting Dennis (apparently from notes), Josephson lays out some gems of provocation:

I have a very low opinion of bankers. If only they weren’t so smug, so full of their pieties! . . . business can’t recover; we are going over a cliff into a terrible inflation, in one year. . . . But Mrs. Roosevelt, Miss Perkins, and the other New Deal advisors look on the U.S.A. as an interesting settlement-house proposition with which intellectual ladies and college professors can divert themselves at the public expense! The New Deal is only a huge muddle—and yet the old trading class, the bankers, the merchants, the politicians, and labor leaders are still in the saddle. . . . It just can’t go on. I tell you, the future is to the extremists. . . But here [the communists] haven’t a ghost of a chance. The working class—bah! The proletariat rise? Not on your life—it isn’t in the beast. The American worker won’t even fight for his class. What this country needs is a radical movement that talks American. Our workers not only don’t ‘get’ Marx, they can’t even lift him.[47]

Dennis—as recalled by Josephson–goes on: only the frustrated middle classes will fight for power; the moneyed people, ultimately facing the perceived threat of socialism or communism, will finally come around in support of fascism as the only alternative: “After all, fascism calls for a nationalist revolution that leaves property owners in the same social status as before, though it forbids them to do entirely as they please with their property. Then, instead of destroying existent skills as would a communist rising, the corporative state would preserve the elite of experts and managers, the people who understand production and can keep the system running.”[48]

As frankly as he advocated fascism, however, Dennis would have no truck with brawling native-fascists of the “shirt”-movement level, nor with religious bigotry or race hatred, in which he was plainly not interested. Rather, he considered his mission as purely one of education and propagandizing to the frustrated middle class out-elite, which will be the real vehicle for American fascism.

On the subject of Huey Long, Dennis noted that “Long reads my stuff” and had asked his help in writing a book on the redistribution of wealth. As Josephson also recounted, after they had finished their conversation, as Dennis was leaving the Harvard Club, he was accosted by an elderly member who exclaimed, “Yes, we all have to stand together and fight for the liberties won by our forefathers who developed the frontier!” Dennis’s polite but brusque reply was, “Remember Mr.——, the frontier is finished; liberty is a dead issue.”[49]

Josephson concluded at the time, and was of the same mind in 1967, that Dennis was brilliant but flawed in his obsession with issues of pure power and manipulation: “An odd and clever fellow was Dennis, but with great gaps on the human side.”[50]

Justus D. Doenecke, a historian of American isolationism and right-wing movements, broke the exclusion of Dennis from consideration in scholarly literature with his 1972 article on Dennis as a “cold war revisionist.”[52] Interested in how the pre-Pearl Harbor isolationists reacted—in different ways—to the cold war, Doenecke concluded that Dennis was a prime example of an isolationist who was consistent in his opposition to American involvements abroad; only Dennis, through his weekly, The Appeal to Reason, “offered a scathing attack upon the entire range of American Cold War policy.”[52]

Doenecke gave careful attention to Dennis’s economic ideas as central to the development of his later positions. After reviewing the arguments of Is Capitalism Doomed?, The Coming American Fascism, and The Dynamics of War and Revolution as to the rise, fall, and inevitable replacement of capitalism by a collectivist political structure, Doenecke noted the similarity at first glance of these to the Marxist critique of capitalism. Yet “the thrust of Dennis’s logic was far from Marxist; there were strong differences.”[53] For one, his “socialism” was not at all utopian, and saw no possibility for a truly “classless” society ever: there would always be leaders and led, and contests would only be over which elites would rule, not whether elites would rule. Under “socialism,” the proletariat would never rule itself but would have to be led by a managerial elite of technicians and experts.[54] (Doenecke might have noted here Dennis’s brand of egalitarianism: his “socialism” would guarantee that anyone with the requisite ability, no matter from what “class,” might join this “managerial elite” without traditional economic or social interferences standing in the way.)

Dennis further dissented from Marx and Marxism in rejecting the notions that the entire capitalist old order of business enterprise should be overthrown in violent revolution and that even if a “world socialist” order should entirely and universally displace capitalism, universal peace would result: “socialist” nations would inevitably fight among themselves, just as capitalist nations do. In Dennis’s critique of the cold war, which stressed the futility of America’s grasp after hegemony in both the world economic marketplace and the marketplace of ideas Doenecke found an early precursor of “New Left” revisionist historians William Appleman Williams, Gabriel Kolko, and Lloyd C. Gardner. Dennis also anticipated the “Red Fascism” thesis of other historians, noting the ease with which “Everything [the interventionist Establishment] said against Hitler can be repeated against Stalin and Russia.”[55]

The first issue of The Appeal to Reason appeared the same week as Churchill’s Fulton, Missouri, “iron curtain” speech; right then Dennis was warning that further American intervention in the world, this time to stop communist sin instead of fascist sin, would result only in the spread of communism—and the intensification of the very domestic “statism” that the conservative cold warriors deplored. At a time—Mao Tse-tung’s march to power in China—when conservatives were seeing communism as a world monolith directed from Moscow, Dennis predicted that rifts would develop in any concert of communist nations, the most important being in the Far East, where existed “nearly a billion people who could never be made puppets of the Slavs, even though they all turn communist.”

Dennis stressed the importance of economic “open door” concerns in the formulation and implementation of the Truman Doctrine, which was designed in part, in the Middle East, to protect Standard Oil interests. Overall, the doctrine served America (which refused to import as much as she exported) as a substitute for the huge foreign loans that Wall Street made in the 1920s in its market-expansion thrusts. “We shall have,” wrote Dennis in 1947, “a limitless market for American farm products, manufactures, and cannon fodder.”[56]

Doenecke continued with an exposition—taken mainly from issues of The Appeal to Reason—of Dennis’s lines on the further development of the cold war, the domestic red-hunting hysteria (he was against it, and held that “Any spy dumb enough to get caught by our F.B.I. is a good riddance for the reds”[57]), the emergence of the Third World as a force in global affairs, and the signs of a gradual “convergence” of both the capitalist U.S.A. and communist Russia (both becoming technocratic, managerial welfare states with planned economies and controlled currencies). With the Vietnam debacle, America’s time had finally come after a “long and brilliant record of success” in empire-building; it was “the beginning of the end of American intervention and overseas imperialism.” Dennis saw his own long record of warnings and observations unfortunately vindicated—by the disastrous turns for America in the world at large.

Dennis’s early and ongoing critique of the cold war demonstrated the consistency of his economic thought from its earliest expositions. He saw the cold war as propping up a capitalism that continued to decline; massive foreign aid, a massive and permanent scale of military production, and a space race were the substitutes that American capitalism concocted to replace the lost frontier. The inflation attendant to all this, whether at higher or lower rates, prevented another crash, and all the activity and spending kept unemployment at acceptable levels. And there was no such thing as significant overproduction in a global cold war, with its “limitless” needs for products both commercial—as allures for prospective “allies”—and military, if those allures didn’t work. The cold war was therefore functional for America—but at a terrific cost and risk. The professed international moral aims of the struggle would not be achieved, and the survival of civilization or of life itself was what was at stake in the great big game.[58]

Rounding off his treatment, Doenecke remarked on many points of prescience and diagnostic acuity in Dennis’s critique. He did criticize other points—notably, Dennis’s persistent faith in a managerial elite as fit to replace the old capitalist/democratic politicians’ elite. Dennis’s analysis “possessed a double-edged sword. The very bureaucratic elite which, in his eyes, should muffle the crusading ardor of the warriors could also be the repository of the mindless dogmatism he so often mourned in the masses. If anything, he overstressed the reasonableness of the new managerial system . . .”[59]) Ultimately, Doenecke was interested in Dennis’s place in intellectual history, and here he saw Dennis as a man before his time, a prophet still basically unrecognized: “He caught the relationship between frontiers and markets at least twenty years before the ‘Wisconsin School’ of diplomatic history was born.”[60] But Dennis’s post-World War II political and intellectual exile may well have contributed to the sharpness of his exposition: cranking out a mimeographed newsletter from his garage, subject to no advertising or editorial or academic pressures whatever, he could say what he pleased. Since that time more people, whether directly influenced by him or not, have been pleased to say it.

Historian Ronald Radosh paralleled much of Doenecke’s approach in the first of two chapters devoted to Dennis in his Prophets on the Right: Profiles of Conservative Critics of American Globalism[61] (The other “prophets” are Charles A. Beard, Oswald Garrison Villard, Robert A. Taft, and John T. Flynn.) The first chapter covers Dennis as “America’s Dissident Fascist” and reviews his 1930s and early 1940s positions and what happened to him during the war from taking them; the treatment of the sedition trial is more thorough than in any others’ discussions of Dennis. Noteworthy also in this regard was Radosh’s consideration at length of the reaction to Dennis’s mature anti-capitalism (as expressed in The Dynamics of War and Revolution) by American communist intellectuals, who took him very seriously indeed. These, while arguing that Dennis’s prescribed fascism would only amount to reactionary state capitalism and repression of the workers, nevertheless could find a lot of truth in his critique of old-style liberal capitalism and the follies of democracy; Dennis’s criticisms were deemed unanswerable by conventional liberalism or conservatism.